All About Timelines

P&D #11: Popular education in a time of remembering connections

Timelines are a fast and democratic means of sharing group knowledge.

Representing events

A timeline is one of the simplest and common means of representing the relationship of events to each other. All events happen at a place and time and it is easy to create a linear timeline on which to place these events. But timelines may oversimplify the complexity of the relationships amongst various events. Also, when using timelines as a tool to generate knowledge from a group you will likely encounter some ambiguities: many people cannot remember exactly when something happened and you may have contradictory (and sometimes inaccurate) information placed on the timeline. You need to decide if your objective is to develop a consensual history (in which case you need to structure workshop time for this) or if you simply want to spark the group’s thinking and refresh the collective memory. It is worth noting that even if information is in some way inaccurate it still represents something important to the person who contributed it.

The easiest thing to place on a timeline is an event. However, this is not as easy for some people as it may sound. For example, many people do not distinguish events from trends and, while an event suggests a place and a duration of time, a trend is not as easy to pinpoint. Where does one place “The Enlightenment”, for instance. Or the advent of a certain idea may also be hard to pinpoint (e.g. women’s right to choose). What you do with these types of issues depends on the purpose of the timeline. If the purpose is simply to facilitate a brief dialogue it may not be important to delve into the difference between an event and a trend. However, if the purpose is historical recovery of a particular group or community then one of the objectives of the timeline is precisely to identify trends. If some people jump the gun and put trends on the timeline then this may be an important assist to the group’s thinking. However, too-hasty identification of trends might eclipse some important events. This suggests the opportunity to challenge the group to add some detail of events that are part of that trend. It all depends on the group’s objectives and the available time and energy.

Structure

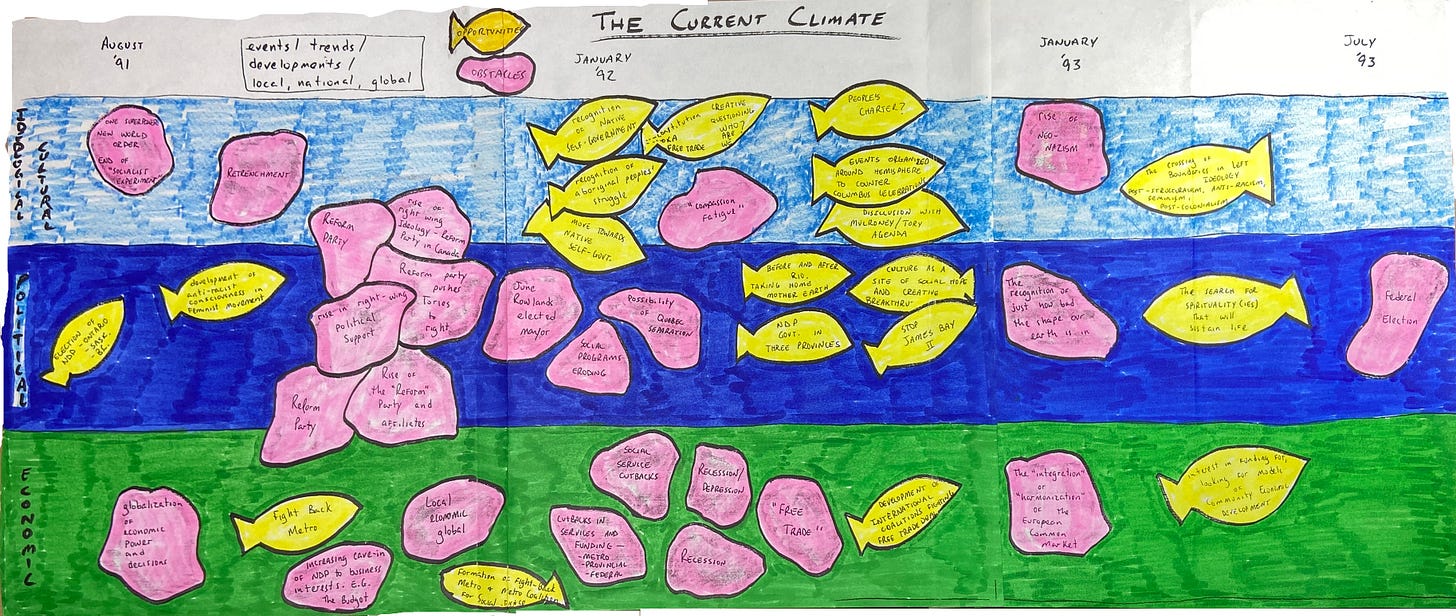

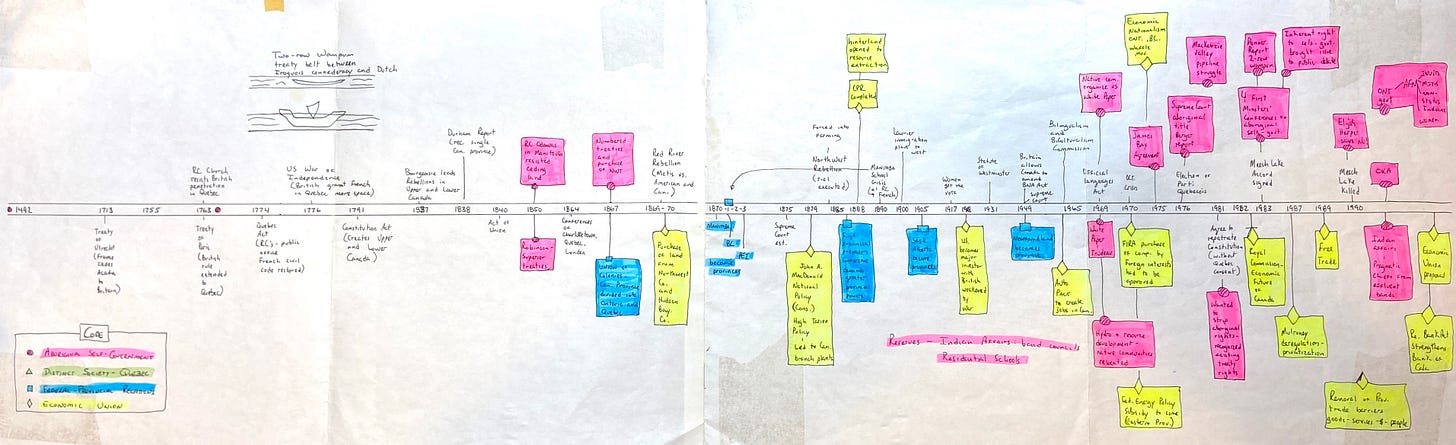

A typical timeline that can be drawn on paper for the purposes of a workshop has only two dimensions. The horizontal axis is divided into units of time (centuries, decades or years). The vertical dimension can consist of two to four rows each of which identifies a particular location or type of event, for example: "Events in Canada" and "International Events"; "Events that Help Us" and "Events that Hurt Us"; "successes" and "failures"; etc.

Another level of complexity can be added to a timeline by using different colours of paper or different shapes to represent different types of contributions. One colour could be identified as representing "events of resistance to oppression" and one as "acts of oppression". One colour could be used for participants to write their names. Cards could be designed using a weather metaphor (e.g. sun, clouds, rain, storms, snow, drizzle, etc.); or a garden metaphor (e.g. seeds, rocks, seedlings, trees, flowers, butterflies, etc.). The more complex the design the more time it will take to explain it to a group and, possibly, for the group to complete. It is always wise to be clear about what you want to achieve through the use of a timeline.

The power of small groups

Recommendation: when doing a timeline with a group, divide participants into pairs or small groups of 3 to 4. The use of small groups has a couple of important advantages: it allows for more discussion - which stimulates memory and it provides the safety of relative anonymity for those participants who feel they “don’t know that much” and therefore might feel intimidated or embarrassed to expose this to the large group. Frequently, participants who start off feeling that they don’t have that much to contribute find the small groups very generative. The important thing is to avoid forcing anyone to share knowledge (or their lack of it) with the group.

From refreshers to historical recovery

A timeline can be used very quickly (as short as 20 minutes) to allow a group to identify key events relevant to the meeting or workshop. The instruction could simply be to ask each person to write on a card the two or three key events that lead to the workshop. This is a good way to remind people what has happened leading up to the workshop or to orient newcomers or to begin to set an agenda. Once all contributions are posted several tings might be obvious: duplications (which might represent widely shared knowledge or shared concerns); more local compared to international events; older versus recent events; and so on. It is also often worthwhile to examine the timeline for what is missing.

Timelines can be used to identify or examine critical questions. You may begin with a specific question, e.g.: why is the group or community losing energy in a particular struggle? Or you can use it simply to generate questions from the the group.

You can also build a great deal of complexity into your timeline. It might be worth devoting several hours to generate and then further develop the timeline with collective critical examination and dialogue about what’s on the timeline, what’s missing, what should be added, what needs research, etc. Hegemonic education teaches that history is written by experts and that history is the record of major political-economic events and some charismatic personalities. Many people do not see themselves as subjects (the makers) of history at all. Thus the historical significance of many actions in a community or group is ignored and oftentimes forgotten. A timeline can be used to recover community knowledge in order to expose and examine the patterns of struggle, defeat and victory in a community’s history.

The power of patterns

A community-based arts organization created a timeline that began when the group was founded. The timeline had three horizontal sections: events in the history of the organization, events in the history of the greater community, and the members of the organization who were present for the workshop. Participants took Polaroid photos of themselves as they arrived at the workshop and pasted them to the timeline where they joined the group. In small groups everyone then completed sticky notes of events for the two “events” sections. Two things were immediately obvious to the entire group upon looking at the completed timeline. There were two noticeable clusters of Polaroid photos: a dozen grouped around the founding year and a second cluster - another dozen - grouped over ten years later. It was instantly clear that there were two distinct generations of membership in the organization. This provoked the question: why? Was it the result of the work of the founding members that took ten years to bear fruit? Or was it because the founding members made space for new members to take leadership? The second thing that was obvious was that there were dozens of events represented in the first ten years of the organization and only a handful in the more recent years. Conversely, there were very few events in the first ten years on the community side and dozens in the more recent years. Again, it was immediately clear to everyone that the hard work of the organization from its inception was, in large part, responsible for the plethora of events that were now happening independently in the community. This allowed people to ask critical questions about how exactly the organization had supported independent community initiatives and what would be most useful for the organization to do now that the terrain had changed so dramatically. This timeline exercise was an important act of historical recovery and was part of a moment of change in the organization's life.

How to Design and Facilitate Timelines in Popular Education Work

There are, of course, many ways to go about doing a timeline. The following description of steps is a typical approach and easily adapted to many contexts.

Objective:

Decide exactly why you want to do the timeline, e.g.: a warm-up to share some basic group knowledge; an orientation for newcomers; historical recovery of community events; etc.

Supplies:

Markers (at least one dozen)

Index-card-size post-it notes or sheets of paper (approx. 5" x 4")

two different colours - one for "helps" one for "hurts"

cutouts of relevant shapes drawing on a metaphor (e.g.: weather, garden, etc.)

Masking tape

Large sheets of paper or several sheets of flip chart (the heavier the better, newsprint is sometimes too flimsy)

Steps:

Post your paper on the wall and divide it with at least one horizontal line along which you can mark your divisions of time. Create as many other horizontal sections as you need and label them clearly. It is also recommended that you label the timeline itself with big letters across the top (e.g. “a people’s history of….” Or “A Timeline of….”)

Introduce the timeline and point out the sections and the events that the facilitator has placed there. You can stress that “personal experience” includes both what has happened to us and what we know about (through family, friends, reading, etc.) that has affected us in some way

Distribute sheets of paper (half of letter-sized page or index-card-sized post-it notes or cutouts)

Ask participants to think of events that they know about. This can be done in pairs or groups of three to make the process more energetic and to aid people in remembering.

After 15-20 minutes ask participants to post their contributions on the timeline. This can be done as a melee with everyone posting simultaneously and after which everyone stands back while volunteers are solicited to share something they posted. Or you could ask participants to begin by choosing one item that they post and explain briefly. Once everyone has had a turn then ask everyone to post the remaining contributions simultaneously.

Museum Tour: once it appears that the majority of contributions are posted suggest that everyone come up for a "museum tour" - to get a general look at the timeline.

After a few minutes ask for volunteers to talk about something they put up. If volunteers are scarce, read some of the examples and ask if the person that put it up would be willing to talk about it. Once the participants have had an opportunity to volunteer more detail, solicit questions about specific contributions that people would like to know more about.

Ask participants what patterns they see – either repetitions, absences, connections from one section to another and so on. List any critical questions or issues that warrant deeper discussion.

Point out that the timeline is obviously incomplete and can be added to at any time. (If you leave the timeline posted for the duration of the workshop, suggest that participants feel free to add to it.

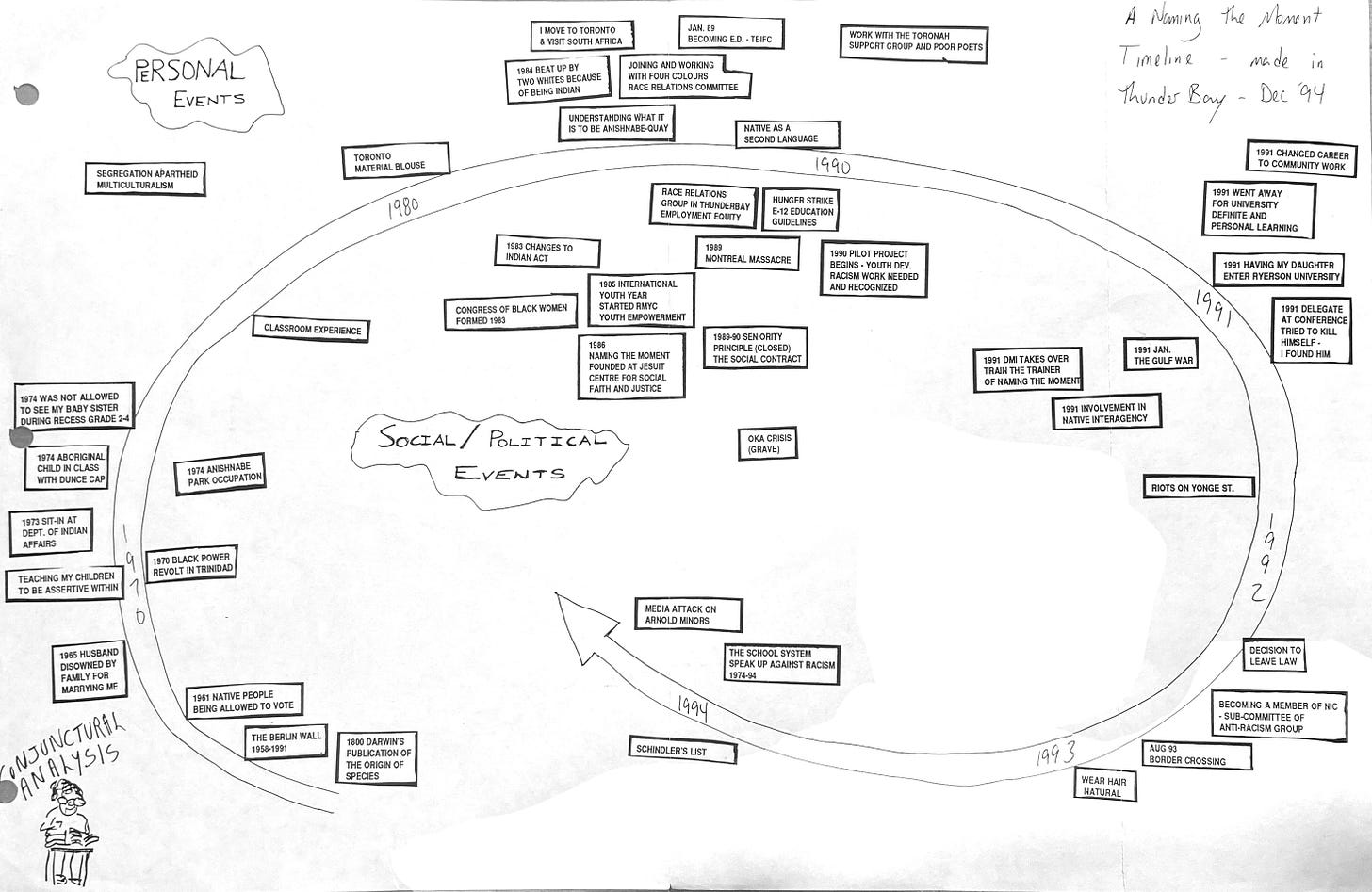

SOME THOUGHTS ABOUT TIME

It often comes up that the linear nature of a timeline is both limiting and biased towards certain conceptions of time. Neither all people nor all cultures share the same concepts of time. In addition to a linear view, time can also be conceptualized as a spiral, as having width and depth, as moving slowly and quickly and as not really existing at all. John Berger writes about time in his lyrical memoir And our faces, my heart, brief as photos:

With the absence of remorseless time and space, the past becomes lost and falls into nothingness. ... God abandons life, to inhabit the eternal domain of death. No longer present within the cycles of time, no longer the hub of these cycles, he becomes an absent, waiting presence. All the calculations underline how long he has already waited or will wait. The proofs of his existence cease to be the morning, the returning season, the newborn; instead they become the "eternity" of heaven and hell and the finality of the last judgement. Man now becomes condemned to time, which is no longer a condition of life and therefore something sacred, but the inhuman principle which spares nothing. Time becomes both a sentence and a punishment.

In a workshop with a group of First Nations agencies the issue of the linear bias of the timeline arose. The design committee discussed different cultural ways of conceptualizing and experiencing time. The committee came up with a spiral design with the beginning of the time line inside the spiral and moving out. This presented challenging logistics since the spiral requires more height than a horizontal line. The poster of the timeline was almost ten feet high and we had to stand on chairs to put things on the spiral. We agreed that on the inside of the spiral we would post events of resistance to oppression and, on the outside, events of oppression. When we examined the finished line we noticed the happy accident that we had virtually drawn a circle around ourselves as represented by the events of resistance. Inside the circle it was easy to connect one event to another while the events of oppression were more isolated being on the outside of the spiral. This gave rise to surprising and very welcome analytical questions that the design committee hadn’t thought of.