TTRPGs and Popular Education

P&D #9: popular education for "staying with the trouble" and fighting dragons

In this issue:

Musings: Popular Education and Roleplaying

Some Favourite RPGS - a list with links

Toolkit: Ring: Telling the Stories of Trees

The Power of Imagination: an RPG anecdote

Roleplaying - Some Backstory

I underestimated the power of roleplaying. And now I'm trying to catch up.

NOTE: feel free to skip this wee meander through my history with roleplaying; you could jump ahead to Roleplaying as Popular education.

Shortly after i discovered the world of Paulo Freire and popular education in the early 80s, I was introduced to the world of Augusto Boal and Theatre of the Oppressed. My practices as a learner and as an educator had undergone almost yearly - more like a few-times-yearly - revolutions since first discovering Ursula K. Le Guin's work when I was 12, Viktor Frankl's work when I was 17, Eduardo Galeano's work when I was 19 and, of course, Paulo Freire's work. Learning of Boal and Theatre of the Oppressed (from Canadian playwright and director - and now newly-minted PhD - Lib Spry) required yet another revolution. I had used skits and roleplaying and socio-drama in activist work up to that point. But I was never comfortable with it. Never being able to put my finger on the nature of the discomfort, i drifted away from those activities that relied on skits and roleplaying. Along comes Theatre of the Oppressed and I was gobsmacked by the power and potential of this method of education and action.

Developed by Brazilian theatre director Augusto Boal, Theatre of the Oppressed is a method of working with non-actors - i.e. members from the community who are resisting some form of oppression - to craft stories of oppression. Through a series of workshops a short play is prepared that illustrates an act of oppression (this can be made up of three or four scenes). The most concise description of the type of story prepared is: the story of someone trying to change their life, but they fail. The key is the failure. This play is presented in its entirety (usually no more than 15 minutes) to an audience. But then the fun starts. The play is presented a second time. But now members of the audience (referred to as spect-actors by Boal) can yell, "Stop," to halt the action and recommend changes. Changes that would alter the outcome for the better. This process is facilitated by a "Joker" who mediates between the audience members and the "actors." Audience suggestions are attempted by the actors or by the audience member - or spectActor - who suggested the change (the latter tends to be the preferred practice) but, more often than not, these changes fail to alter the outcome. Occasionally they succeed. But therein lies the wonder and magic of Theatre of the Oppressed. It is a dialogue about oppression and resistance through the medium of theatre. The many suggestions made for different actions in the play are typical of the common sense of the audience members. But what common sense dictates often fails to halt the violence and oppression. But witnessing this failure can be a transformative moment for many people. One that moves them ever closer to action that might actually succeed in real life. I could go on and on. But will share more about Theatre of the Oppressed in a future issue of this newsletter.

I have practiced and studied Theatre of the Oppressed for almost 40 years now. And yet, it is only recently that the penny dropped about the power of roleplaying. It is perhaps a case of not seeing the forest for the trees. My love of Theatre of the Oppressed blinded me to a much wider world of radical potential in roleplaying. My enlightenment began in 2015 when my son was seven-going-on-eight. I had been observing his use of computer gaming which was mostly Minecraft but also included several other video games that he played with his siblings and friends. Typical for him and his peers (if not entire generation) his time spent on these games was increasing steadily. Like many parents, I was concerned. But I also knew that limiting his use of these games was a strategy fraught with peril. So, taking the advice from the proverb, "you'll catch more flies with honey than with vinegar," I wondered if tabletop roleplaying games might act to counter his increasing time with video games. I began researching Dungeons and Dragons. Having spent my teen years in suburban Montreal, I was effectively isolated from many North American cultural phenomena. Thus I didn't learn about D&D until i was well into my 20s. And now, looking at it in 2015, I was rather intimidated by the amount of information that needed to be mastered to be able to run a game. Also, it appeared that D&D was geared to teenagers. I searched hard for roleplaying games suitable for 8 or 9 year-olds but there was little to be found.

Then I found SimpleDND. It was perfect. I was able to create a campaign for my son and his friends that was easy to explain (in terms of rules) and quick and fun to play. I continued to search for materials suitable for 9/10 year-olds. Dungeons and Dragons had released its Fifth Edition in 2014 and this began a renaissance for both D&D and many other RPGs. It took a few years but by 2018 I started finding more and more material geared for younger ages. Only by then I had concluded that it was best not to introduce these games to kids younger than 9. My conclusion, though limited to my observation, is based on witnessing the dynamics of unstructured make-believe play. Such unstructured play is crucial to how kids learn many things and i am loathe to mess with that. Table-top roleplaying games are highly structured experiences and these can easily interfere with the relatively less structured play-worlds of the young. Nonetheless, I learned enough to confirm my hypothesis that tabletop roleplaying could act as a counter to the domination of digital games. “Truth to tell, I would choose a four hour D&D session over any video game,” says my son. I will share more on this another time.

We've been playing D&D now for over 5 years. And it proved a lifesaver when the pandemic hit as we moved our games online and we became quickly adept as the pandemic endured. My research deepened and grew and as I began my PhD it was obvious that I would have to include a reassessment of role-playing in the world of popular education.

Roleplaying games as popular education

Popular education has always included a variety of forms of popular theatre from relatively unstructured (e.g. spontaneous skits) to highly structured (e.g. Theatre of the Oppressed). Some people love this aspect of learning and are quick to volunteer and immerse themselves in this playful way of learning. Many are less than eager. Thus, having witnessed plenty of examples of popular-theatre-gone-wrong, I have learned to establish early on in any learning process the "right to pass" or to "deselect" from a game. I almost always point out that in deselecting from a process there is the opportunity to serve the group by being a process observer. This usually succeeds in including almost everyone in the process. For years this served to allow me to avoid some of the riskier ground of roleplaying. This risky ground is almost always a consequence of patriarchal power, class privilege, racism, ableism, ageism, and legacies of colonialism which can include all of the preceding forms of power. Given that popular education is, at its core, about resisting unjust uses of power, it is certain that one or more (usually more) of these relations of power (or, to put it another way, relations of oppression) will be confronted and require a group's attention. It is common now to see learning experiences begin with identification of "group agreements" that include discussion and affirmation of safety protocols available to all participants.

But while popular education has been slowly developing a culture of safety, support, and ethical behaviour, the world of roleplaying games has been charging ahead. The two dominant forms of roleplaying games, excluding digital/online media for the time being, include tabletop roleplaying games (or TTRPGs) and live action roleplaying (LARP). Both TTRPGs and LARP have developed various systems of rules that structure the gameplay as well as build in various forms of safety. (I will discuss LARP, especially Nordic LARP, in a future issue of this newsletter - hint and tease: it includes my very short career as a model). As I delved deeper into research on RPGs I saw that there was an enormous amount of learning going on through these games. And I began to wonder about the pedagogy of RPGs. After several years of research, I've only scratched the surface. There is a young but growing field of scholarship about this field. But the field itself has been growing by leaps and bounds. The COVID 19 pandemic has, perhaps ironically, been a boon for RPGs. Given the necessary social isolation practiced during the pandemic many people took advantage of remote communication technologies (like Zoom, of course, and Discord) to connect online to play games. It turns out this works quite well. My son and I have run several D&D campaigns online and, while the loss of the in-person experience is unfortunate, online communication allowed us to include friends across the continent. And, while roleplaying games usually involve several people (groups of 3 to 7 are most common) game developers have created an astonishing variety of solo roleplaying games.

While Dungeons and Dragons (which was created in the early 1970s by blending wargaming with sword and sorcery fantasy) dominates the field of roleplaying, there are now games based in numerous genres from fantasy and science-fiction, of course, to mystery, horror, folk-horror, farming, historical fiction, and more. And there are an ever-growing number of rules systems from simple to complex: D&D’s D20 System, Powered by the Apocalypse, Tiny D6, Gumshoe, Cypher, Cortex, Wretched and Alone, and more all the time. All of these rule systems have a couple of things in common: they depend on character creation (which can be simple or complex, chosen from a menu of choices or created from whole cloth; and they facilitate the creation of an immersive experience of storytelling and game play. It is this combination of character creation (which is what the players are roleplaying, after all) and immersion that is key to understanding how RPGs are different from literature, theatre, or storytelling.

This brings me to the connection with popular education and why I think TTRPGs solved a problem with how roleplaying was (and continues to be) used in popular education as well as other forms of learning. The creation of characters results in players having a strong emotional bond with their creation. These characters are roleplayed in an immersive imagined world and confronted by any number of challenges (from monsters to lost treasure to simple survival in a dire environment) while governed by a rule system that creates structure and process for collaborative engagement (with as much safety and risk as players deem necessary). This creates the conditions for complex tactical and strategic thinking that actually has consequence with characters suffering damage (which can include character death) or earning rewards (which allows for character growth and change). Also, given the social nature of the game, there is the meta-level of having to share the play space with others. Many of these games are facilitated by either a Dungeon Master/DM (in the case of D&D) or a Game Master/GM (in other systems). This DM/GM role entails game direction (especially facilitating the collaborative storytelling), rules enforcement and arbitration, and the social dynamics of hosting and hospitality. It is a fascinating role not unlike that of Joker in Theatre of the Oppressed. I have a long way to go in examining these games and exploring the implications for popular education.

Meanwhile, i would love to learn of any engagement with these games that you might have had. Have you played RPGs? Do you have a favourite? Have you used them or seen them used in educational settings? Please feel free to respond in the comments.

I plan to share a lot more about RPGs in future issues of this Persuasions and Designs newsletter. Feel free to suggest what you would like me to focus on.

Some Favourite RPGS - a list with links

To conclude this ramble about games, below is a selection of games that I have collected. I have been particularly interested in those games that deal with social justice issues, environment and ecology, gender and sexuality, identity and interpersonal relationships. I have collected hundreds, played dozens, and am developing some of my own. My son has written his own adventures. And there is a worldwide community of creators busily producing hundreds of RPGs a year. The two principal online publishing platforms for RPGs are DriveThruRPG and Itch.io. Have a look at these sites and take a gander at the abundance and wild diversity of what is being produced. Some of my favourites include:

Ring: Telling the Stories of Trees

a popular education toolkit

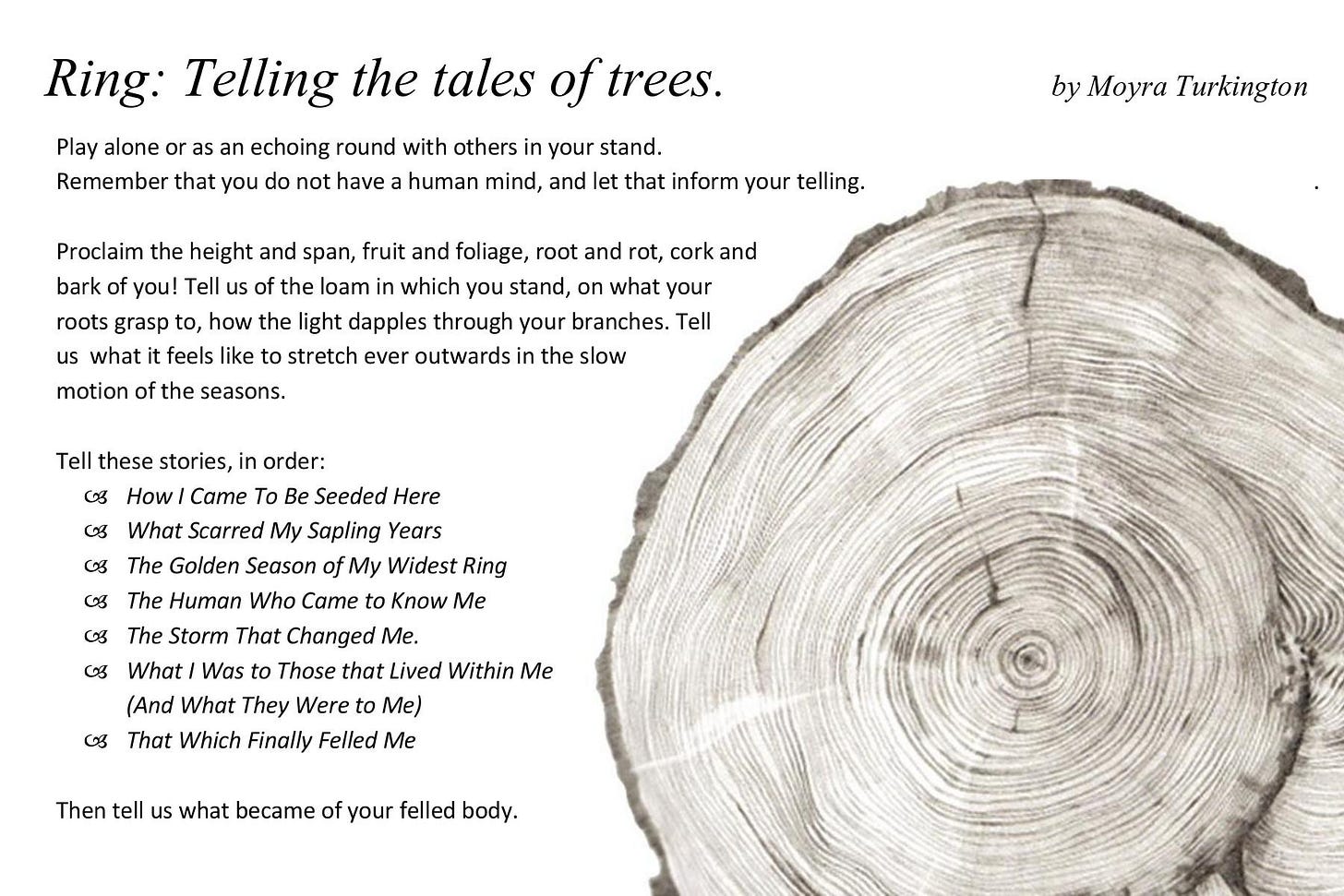

I came across this solo RPG in a collection of 200 Word RPGS. As you can guess, these are minimalist games. Some are for several players and many are solo experiences. This one can be used in either context. Written by game developer Moyra Turkington, a member of Toronto-based games company Unruly Designs, this short RPG is perfectly suited for use in environmental education. I've used it several times over the past few years in various teacher training workshops and with my son and his friends when we ran an on-line (Zoom) Ish School (school-ish, get it?!?!) in the first weeks of the pandemic lockdown. I've also used Moyra's RPG as a model for writing other experiences for engaging aspects of the natural world such as rivers, fungi, forests, glaciers. The first time i used this in a teacher training workshop the participants embraced the 'game' with gusto. All participants shared quite moving responses and one pair did an interpretive dance. It was awesome.

All you need to run this ‘game’ are the instructions in the above image. But just in case, here's the entire text:

Play alone or as an echoing round with others in your stand.

Remember that you do not have a human mind, and let that inform your telling. Proclaim the height and span, fruit and foliage, root and rot, cork and bark of you! Tell us of the loam in which you stand, on what your roots grasp to, how the light dapples through your branches. Tell us what it feels like to stretch ever outwards in the slow motion of the seasons.

Tell these stories, in order:

How I Came To Be Seeded Here

What Scarred My Sapling Years

The Golden Season of My Widest Ring

The Human Who Came to Know Me

The Storm That Changed Me.

What I Was to Those that Lived Within Me (And What They Were to Me)

That Which Finally Felled Me

Then tell us what became of your felled body.

The Power of Imagination

an RPG anecdote

We sat down for our first Dungeons and Dragons game when my son and his friends were 9 years old. I had done extensive RPG research and prepared everything I thought we needed as thoroughly as possible. I took to heart the importance of creating an immersive story with which the players could engage and have fun. But I was learning as much as they were so .... baby steps. Using SimpleDND I created an adventure based on a favourite Jewish folktale called The Palace of Tears. But this was a grand adventure and I thought it best to start off small. I created a very simple encounter that I thought would "teach" the rules and method of gameplay. We had planned a three-hour session but i quickly began to worry it was not enough time. The first step was character creation and i was simply amazed at the enthusiasm with which these 9 year-olds went to work. They spent over two hours designing their characters and it was beautiful to behold. We could have ended the session right there and they all would have felt their time was very well spent. But i thought it important to give them a taste of an encounter so they could take their characters out for a spin, as it were. I began the game and narrated, "You are walking along a road that borders the forest when you notice some white substance lying across the road. As you get closer you see that it resembles rope and you can see strands in the field between the road and the forest. What do you do?" One of the players says, "I touch the stuff." I explain that it's sticky. Another player says, "I walk towards the trees to see where it's coming from." I narrate: "As you step off the road and walk towards the trees you see six giant spiders emerge from the forest and rush towards you...." Well i didn't have time to ask, "What do you do?" In an instant all the players had leapt - literally - from the table. They each grabbed toy swords or sticks that we had lying around. All of them simultaneously began battling the spiders and I swear i thought i could see the spiders apparate in the middle of our living room. Spider limbs were hacked left and right. Ichor splattered the book cases and splashed into the eyes of our heroes. Each of them were shouting descriptions of the damage they inflicted. It was mayhem. I knew better than to try and interfere. I let the energy run its course. And eventually everyone settled back to the table, spider carcasses splayed liberally around the house. And that was all we had time for that day. The adventurers felt like they had had great success and all had a swagger to their step as they bid adieu and "until next time." And I realized that all the carefully crafted plans to ensure engagement and immersion were utterly superfluous for children that age. All I needed to say was "giant spiders" and their imaginations exploded like bombs. And i realized that while adults might need rules and instructions and support to be able to "suspend their belief" and immerse themselves in the imagined game-world, kids already pretty much LIVED IN that game world.